Note: This article will be featured in a forthcoming publication released as part of History Colorado's Building Denver Initiative.

In the midst of current upheaval and challenge, recent history directs us to a promising reason for hope. Over the past two generations, and especially now, in real time, new development patterns have taken root along the banks of the South Platte River that suggest a future with a socially, ecologically, and more economically sustainable built environment. Our recent history reveals the ten-fold return of bold investments in public infrastructure and provides perspective on opportunities that face society today—opportunities to be met with optimism about what can be achieved when an open and diverse community collaborates together and in harmony with nature.

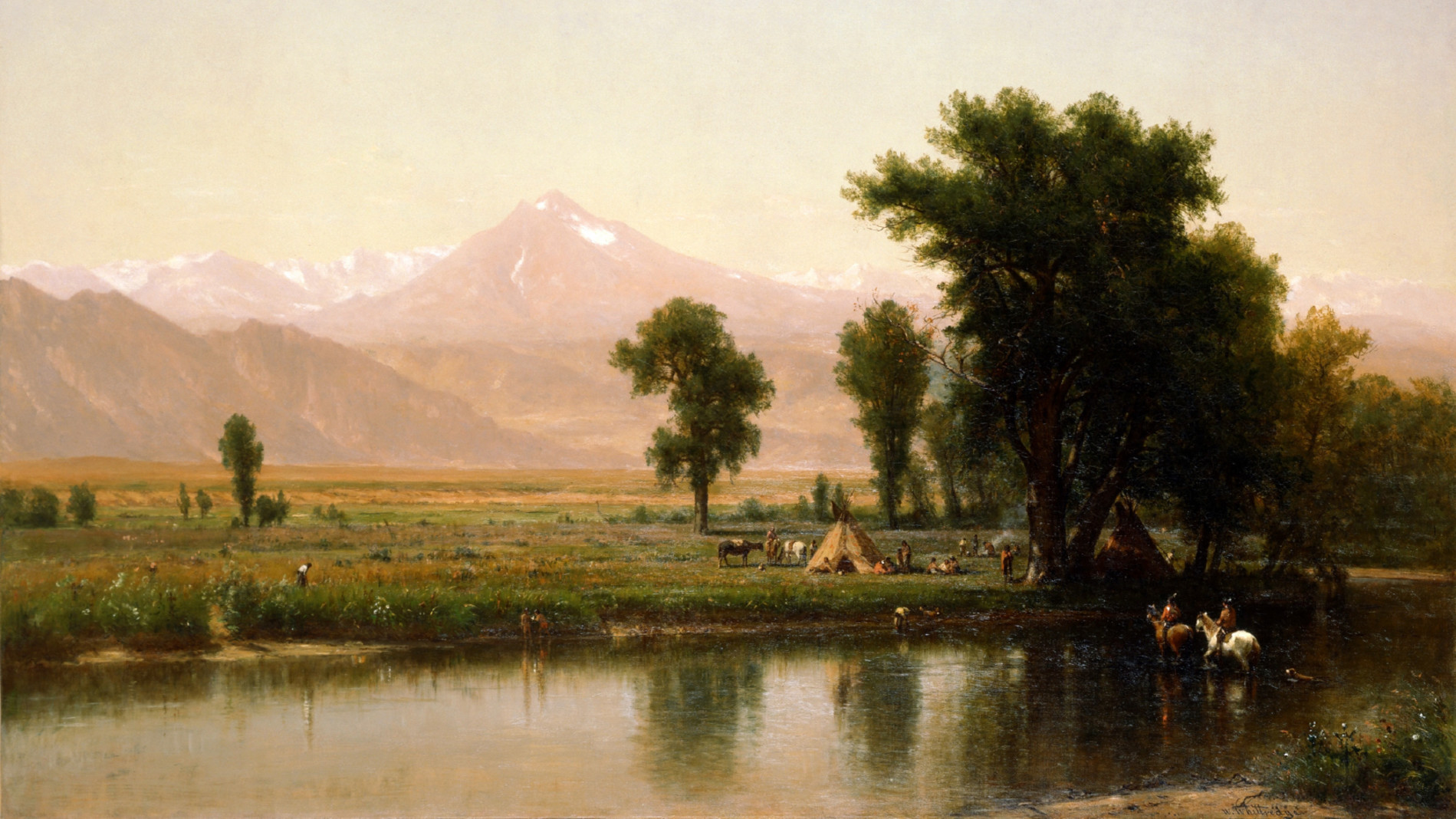

In the Industrial Age, new cities were often positioned on the banks of rivers, lakes, and oceans. Water gave rise to industry and pathways of commerce, indicating where factories and railroads were required to converge and where waste could be dumped. Denver was no different. The Platte River offered prosperity and progress. Denver’s economic boom of the late nineteenth century justified the extensive network of railyards, warehouses, breweries, and coal yards that sprang up along the banks of the South Platte River. Yet livability in this new industrial city was challenging.

Perhaps no one contributed more to making the industrialized city livable than American landscape architect and social critic Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903). Olmsted saw industrialized cities as an inevitable part of the future, and in 1870 he forewarned the American Social Science Association: “…the further progress of civilization is to depend mainly upon the influences by which men’s minds and characters will be affected while living in large towns.”

His biographer Witold Rybczynski writes: “Olmsted concerned himself with the big picture. Large cities were inevitable, of that he was sure. The question was how to make them livable, and how to influence ‘men’s minds and characters’ so that civilization would prosper. …Olmsted was certain the booming industrial city would continue to challenge its inhabitants.”

Olmsted’s vision and answer to the dehumanization of these industrial cities was long-range and imaginative. While he may be best known for Manhattan’s Central Park and Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, he also foresaw the need—and led the movement for—a national park system. His life’s work was devoted to the future promise and engagement of natural landscape into cities to offer equitable and inclusive spaces for all urban dwellers. Olmsted’s legacy is felt in Denver as it was across dozens of cities across the United States, directly and indirectly, in the City Beautiful movement integrating nature within the urban landscape.

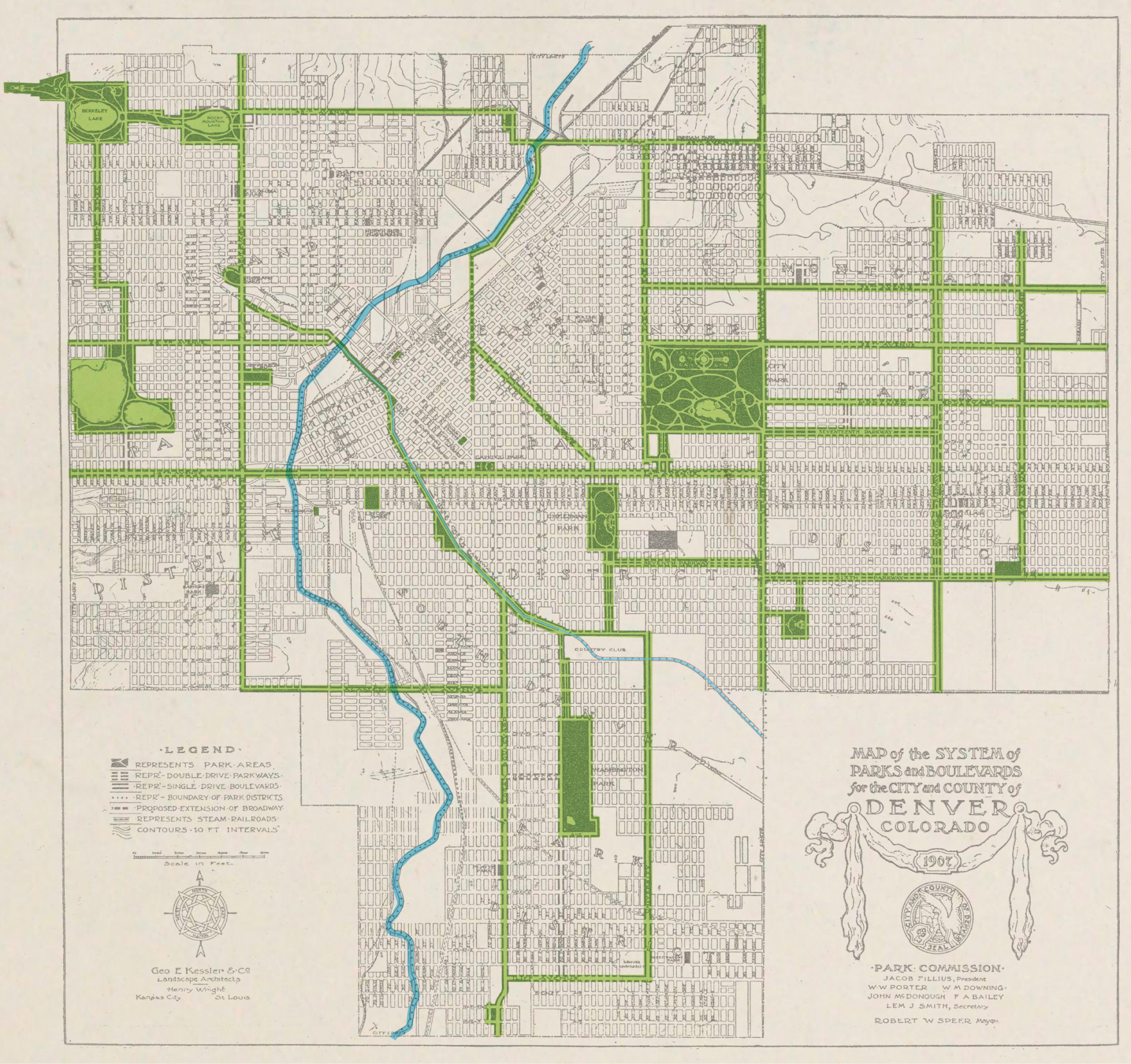

In 1904, at the height of the industrial era when people believed their city was ugly, Mayor Robert Speer created the City Beautiful parks and parkways system, Denver Civic Center, and launched an urban forestry program that gave over 100,000 trees for residents to plant. Denver joined a national effort to find equilibrium between the natural landscape and the evolving industrial city and created the structural framework for an urbanized nature that defines many American cities to this day. Yet, for over 100 years, Denver, again like most American cities, ignored the river or perhaps just didn’t see the possibilities of these natural resources beyond their roles as spines of industry.

The Muddy River in Boston was similarly clogged and polluted in the 1870s by adjacent industrial development when Olmsted made the bold recommendation to reinvent the waterway with sculpted and planted riverbanks, a sequence of ponds, and walking paths. By 1900, the Muddy River Improvements were completed as a central feature of Boston’s famed park system: The Emerald Necklace, reconnecting the industrial city with nature.

Following the lead of much of the rest of the country, Denver continued to turn its back on its primary natural resource, the Platte River, and continued to pollute the river with industrial waste and careless negligence throughout the 20th century.

In 1964-65, Mother Nature offered the opportunity for a new perspective which ultimately precipitated a movement toward the now more promising future of the Platte River. Although the Platte was known for its unpredictable nature, the Great Floods of 1964 and 1965 were a metaphor for the upheaval of the era and caused incalculable damage to Denver’s central core. Across the country, an environmental reawakening was underway, when in 1969 the Cuyahoga River, which emptied industrial waste into Lake Erie, caught fire.

As we faced these environmental challenges, leaders across the country were imposing a new brand of social and physical destruction that came to be known as ‘Urban Renewal.’ In 1968, at the height of the social unrest of the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War, the prevailing response to urban challenges was to wipe the slate clean. In downtown Denver, 27 contiguous blocks were destroyed, obliterating the embodied energy of more than 100 years of artistic, social, and physical structure of the existing neighborhood in exchange for an idealistic and universal vision of the reigning international style of high-rise structures symbolizing a more promising future.

If the Industrial Age was expressed in the riverfront factories and railyards and an ingrained class system, the late 1960s were expressed with an emerging, cold new architecture of placeless buildings and plazas devoid of nature and without regard for human scale. These lifeless towers replaced the lively walkable familiarity of the diverse downtown community. The Urban Renewal Master Plan further mandated bridges over streets to avoid any interaction between cars and people. Upper and middle-class families fled city centers across the country for the homogeneity of the suburbs.

Then, a remarkable turn of events began taking place in the 1980s. Denver reversed the prevailing national trend of the wholesale demolition of historic neighborhoods, working with community leaders to save and redevelop what remained of the city’s historic downtown. Lower Downtown (LoDo) became a national model for the then-radical idea that stewardship of history and the built environment could be the foundation for the city’s future. Vast railyards adjacent to Lower Downtown and the historic Union Station in the Central Platte Valley became the focus for reinvention and new development. The pioneering 1991 Central Platte Valley Comprehensive Plan consolidated 35 tracks used by five different railroads and the public funded the removal of several viaducts spanning the Platte Valley.

The city purchased warehouses and large tracts of industrial land along the river and transformed these areas into what we now enjoy as Commons and Cuernavaca Parks. These public investments began the transformation of the railyards and warehouse district into what has ultimately become a national model for reconnecting urban development with natural infrastructure.

The successful redevelopment and reopening of Denver’s historic Union Station as a national mixed-use destination was led by the $450 million public investment in the regional transit hub behind Union Station just two years earlier. The combined impact of the public investments to transform the Platte River Valley resulted in a ten-fold burst of private investment, further reconnecting the urban core and the many historic neighborhoods along the river.

International companies like Facebook, Amazon, and VF Corporation have made their new homes in the new development along the Platte River. British Petroleum, an international company having made a commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050, relocated their North American headquarters from Houston, Texas to the Tryba-designed Riverview Building, a new structure fully engaged with the Platte River, the emerging new park system, and the adjacent historic neighborhoods as a reflection of the new trajectory and values BPX Energy hold as a company. The Riverview Building was conceived as a series of layered systems—topography, hydrology and water management, circulation, structure, and views at multiple scales—all fully integrated with the landscape and the optimism of a new kind of city fabric profoundly connected to nature and the historic social fabric that has become necessary to attract the best and the brightest young talent.

Building on these successes, new ideas have taken root further north along the Platte River. A public/private partnership added the new 3.5-acre RiNo Park to Denver’s growing network of green space. Again, historic warehouses within the park have been repurposed to house a new public library and a contemporary art center that fosters education and engagement between artists and residents.

RiNo Park has become a catalyst for the new mile-long Promenade of privately funded and publicly connected park spaces now under design and construction throughout the emerging northern section along the Platte River. The RiNo Promenade will link a series of outdoor rooms with festival space, cafes, outdoor art and public access to the river.

These investments in open space are attracting development of a new city fabric, fully engaged with nature, on previously industrial and now vacant land.

In 2017, City Council offered a new density bonus as an incentive to develop affordable housing in RiNo. The rezoning of River Mile in 2019 to the south of Union Station established even higher density in exchange for providing 20 percent affordable housing.

Finally, to the most northern parcel in Denver, the reimagined National Western Center is a crowning example of converging public interests, institutional and private planning, financing, and development. The $2.4 billion complex merges nature and water resource management with the science and industry of agriculture, bringing education and opportunity to the historic North Denver neighborhoods.

Over the last two generations, Denver has embraced a diversity of ideas and leadership resulting in bold public investments unleashing ten-fold private sector returns. Through the stewardship and reintroduction of the city’s natural landscape and the reconnection of adjacent historic neighborhoods, Denver has created a new defining image of the City in Nature, offering a healthier and more restorative urban ecology of place.

This remarkable story embodies the cycle of early development, industrialization, abused natural resources, and finally the recognition that these resources can be reclaimed and nurtured for the betterment of the human and natural environment—the foundation of an inviting “Clearing In Our Midst.”