As the recent global health crisis recedes, new attitudes and technologies continue to transform the way we work, learn, shop, and socialize. Shifting toward a virtual world has disconnected us in unexpected ways, revealing the basic human need for genuine, real-life interactions and experiences. In an increasingly virtual and segmented society, how can cities re-emerge as places of human connection?

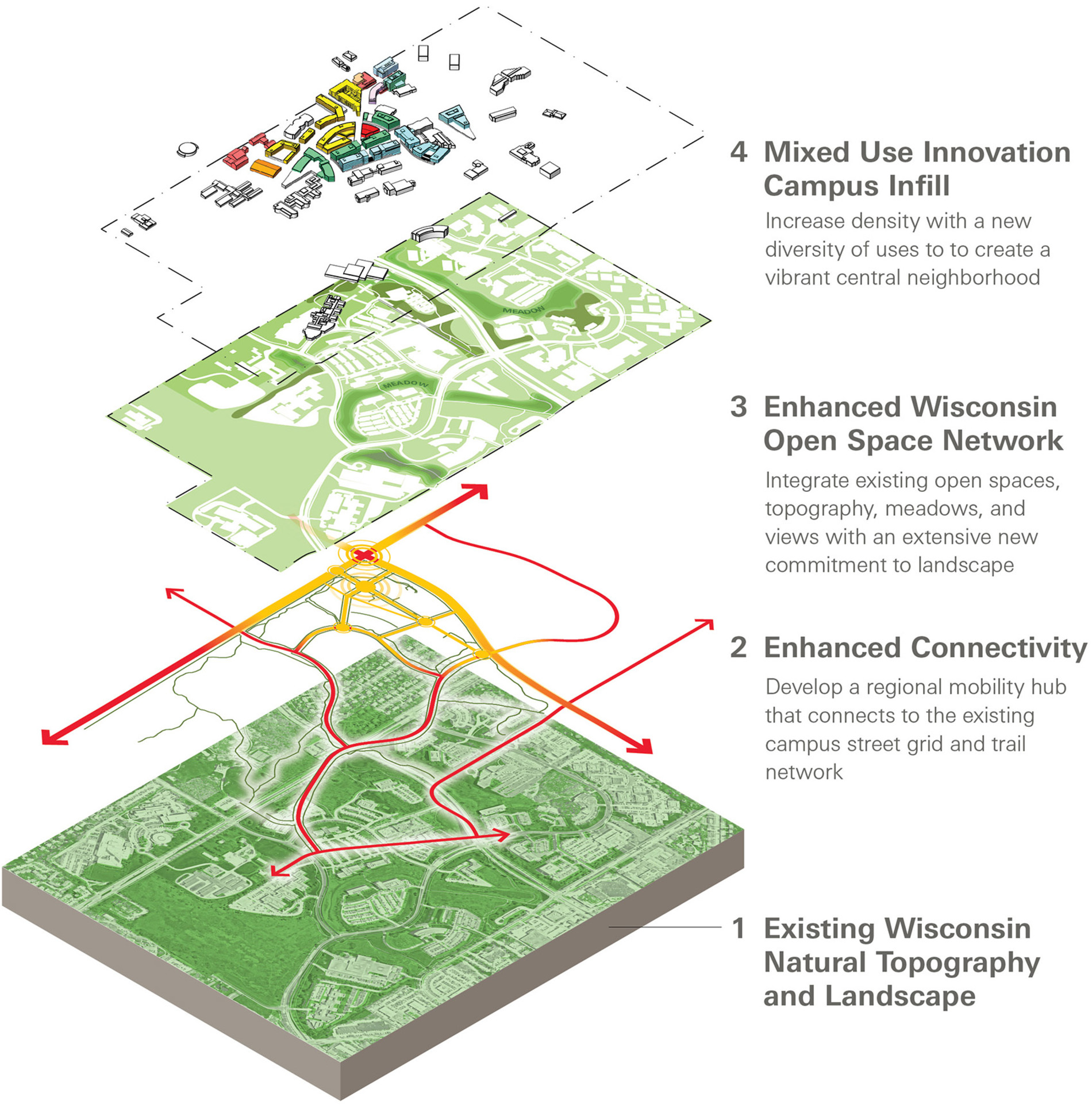

A broader perspective through history shows the most resilient cities have evolved with new technologies and societal changes while enhancing connections to nature and building on cultural and physical assets. As we navigate today’s uncertainties, there is reason to be hopeful if we examine how successful cities have understood and leveraged unique layers of authenticity to attract people and to inspire an enduring sense of community and belonging.

For thousands of years, cities have been shaped by geology, geography, climate, and numerous cultural factors. Rooted in necessity, regional adaptations over time have given places their distinguishing character. Local materials fashioned into red-tile roofs and stone facades of Florence and Milan are case studies in physically cohesive urbanity. Centuries ago, cities in Japan achieved their unique character by constructing with local timber and building in balance with nature to create a ‘garden city.’ Established 2,000 years ago, London and Paris have evolved into vital, contemporary cities that retain their context and preserve their unique identity.

As the world’s population continues to expand, the increasing demand on materials, energy and resources drives the need to build urban areas with more flexibility and efficiency. Across the globe, cities continue being constructed based on the ‘clear-cutting’ and ‘blank slate’ approaches that emerged in the mid-twentieth century, leading to homogeneity and the disappearance of local materials and culture while predominately introducing new buildings devoid of regional identity for the sake of being ‘modern.’ Nature and history are preconditions of self-identification. Regions and cities can distinguish themselves by adopting architectural identity based on authentic place rather than imported from elsewhere. A rich and cohesive conversation among buildings and the natural environment using local materials fosters in their inhabitants a sense of civic pride and emulates cities that are truly world-class.

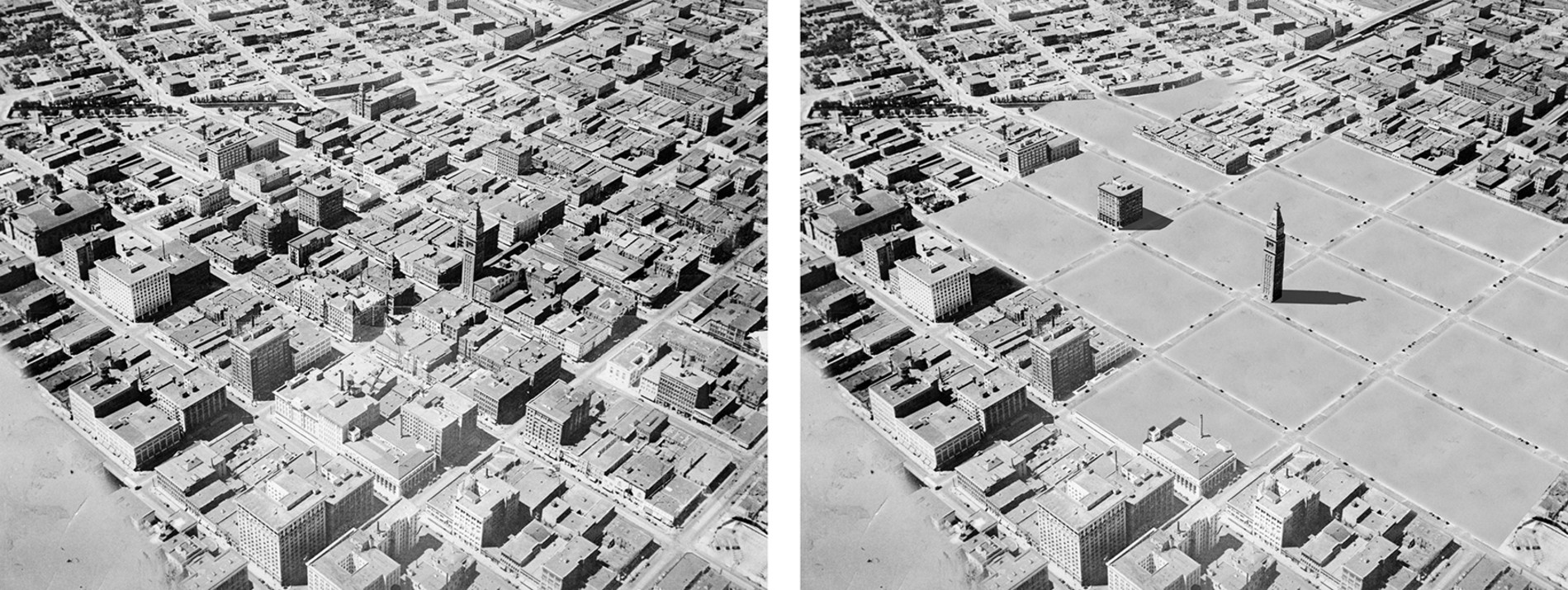

Watershed moments in history push people to think in new ways. The years following World War II were, for most Americans, a time of unbridled optimism as an eagerness to shed associations with the Depression and War brought forth an attitude of ‘out with the old, in with the new.’ In cities, this optimism was expressed through interstate highways, boundless suburban growth, and massive urban renewal initiatives across the country that erased much of the physical and cultural history of our cities in the process. A half-century of this experiment has revealed that not only is ‘starting over’ detrimental to the environment, but that wholesale destruction of cities and systems challenges our fundamental identity and diminishes the human connection to place and to each other.

Offering an alternative approach, in 1978 Christopher Alexander and colleagues published their inspiring classic A Pattern Language, noting that cities “cannot be ‘designed’ or ‘built’ in one fell swoop,” but emerge organically and contextually over time. Rather than building in isolation, authentic places are shaped by their surroundings, leading to coherency and wholeness.

Adaptive reuse and repositioning contribute to preserving and achieving this cohesiveness. Integrating new uses and structures into existing infrastructure leverages the resources, energy and craftsmanship of prior generations while contributing to the financial feasibility of a project. Preservation and adaptive reuse across scales actively create centers of community life, providing economic vitality and an inspiring context for new places and designs. The opposite of freezing places in time, urban repositioning reuses whole systems—not individual relics—that provide a starting point for constructing relevant, contemporary places that respond to evolving contexts while reinforcing culture and strengthening community.

The postwar quest to build ‘bigger and better’ and erase anything considered obsolete has since become deeply ingrained in American life. Office towers featuring concrete plazas and sky bridges loom over streets that channel traffic to interstate highways and widely-spaced suburban homes—all contributing to the demise of the human-scaled pedestrian character of downtowns.

There are numerous ways to reintroduce human scale, making city life more comfortable and inspiring once again. Understanding a site’s context helps to guide decisions on proportion, rhythm, and movement through space. Human interactions with architecture are sensory and tactile, and therefore we are most drawn to places designed to make us feel comfortable and in control of our environment.

Isolation brought by automobile culture still characterizes nearly all urban areas and is now a 'fact of life.' However, a new paradigm is emerging that envisions streetscapes more vibrant than ever before. Transforming singularly auto-oriented roads into fully-amenitized, multi-modal streetscapes can produce attractive and walkable new outdoor gathering spaces. Introducing transparency and interweaving access, transportation, and the ability to live in proximity to work/school, culture, and nature creates vital new opportunities for face-to-face connection. Designing to human scale underscores the importance not only of buildings, but of the spaces between them to begin to reintroduce ourselves to a rich and diverse urban mosaic.

A May 2020 survey from the Knight Foundation asked respondents what makes them choose to stay in a city. Cultural amenities were overwhelmingly selected due to their ability to “boost various indicators of attachment, from higher feelings of satisfaction and personal fit with the city, to behaviors such as greater investment of time and resources in the community.” Civic and cultural spaces help define who we are as a community and contribute significantly to a lively and meaningful public realm.

While our homes and workplaces are necessities for living, it is our cultural assets that allow us to thrive. Cultural variations in language, food, music and art enrich our lives with new ideas and perspectives. As architects of museums, botanical gardens, and other civic and public spaces, our responsibility is to support cultural stewardship and to create welcoming places providing memorable shared experiences that reinforce the fabric of their communities.

The natural landscape is the single most defining characteristic of any city. Every city began as a direct response to the natural opportunities of location. Designing places that are shaped by their specific environment leads to natural differentiation and authenticity. Local topography, hydrology, climate, sun and shade invite customized design responses. Architecture and infrastructure agnostic to specific place leads to generic commonalities that divorce people from their natural environment.

Fundamental to our practice is designing buildings in collaboration with nature. Access to fresh air, natural light, and visual connectedness to the natural world are key to human wellbeing. Gardens, courtyards, green roofs and parks stitched into dense urban environments where people live and work reinforce connections to the natural world. Landscapes that elevate human experience inspire stewardship of the environment and reverence for the living world surrounding us.

The dichotomy of the City being in opposition to Wilderness must be inverted to recognize cities are part of our larger ecology. Landscapes become functional through the use of native plant material for shading and rainwater filtration, food production and, perhaps most overlooked, the sheer beauty of being an integral part of nature, pointing the way toward a more sustainable urban ecology of place. As Sir David Attenborough reminds us, we must relearn to cherish the natural world, because we are a part of it and we depend on it.

The most successful cities throughout history continually change. These cities embody timeless qualities intrinsically linked to geography, culture, tradition and memory. As digital technology beckons us toward a virtual world, it becomes ever more important to restore inviting and inclusive real-life communities. Layers of history and authenticity provide the blueprint for building contemporary urban environments that integrate context and character shaped by a rich diversity of people, places, ideas, experiences, and perspectives.

The experience and depth of leadership at Tryba, like never before, allows us to gauge, balance and manage risks and opportunities, and to see into the future of housing, the workplace, and buildings shaping culture and the public realm. Working across scales of design, we are leveraging the timeless lessons of authentic places to build enduring, human-scaled, contextual communities where people live, work, connect and thrive.